Through a recent podcast, I was reminded of a TED talk given by Niro Sivanathan, a professor of organizational behavior at the London Business School, in which he introduces two hypothetical students. One student “studies 31 hours per week outside of class,” while the other student “studies 31 hours per week outside of class, has a brother and two sisters, often visits grandparents, went once on a blind date, and shoots pool once every two months.” When asked which student they believe will earn a better grade in the class, on average people choose the first student. But why? Both students study the same amount.

Diagnostic vs. Non-Diagnostic Information

As it turns out, our brains are not as great as we might suspect at separating “diagnostic” information from “non-diagnostic” information; that is, information that helps to illuminate the issue at hand from information that does not. In Sivanathan’s example, the number of hours studied is diagnostic. The non-diagnostic information is all the other stuff — the number of siblings and the frequency of other various activities. When we consider the second student, we encounter a mix of diagnostic and non-diagnostic information, and when that happens, a kind of mental dilution occurs. This is aptly named the “dilution effect.”

On the question of which student will earn a higher grade, the argument for the second student loses potency because our brains fold in the less potent non-diagnostic information with the more potent diagnostic information. The first student’s case retains peak potency since we are purely presented with what matters to the issue at hand — the student’s study habits.

But as with most things, the distinction between diagnostic and non-diagnostic information is not always binary. It’s often a spectrum, where certain arguments are strong, and others, while still diagnostic to some degree, are weaker by comparison. What happens in these cases?

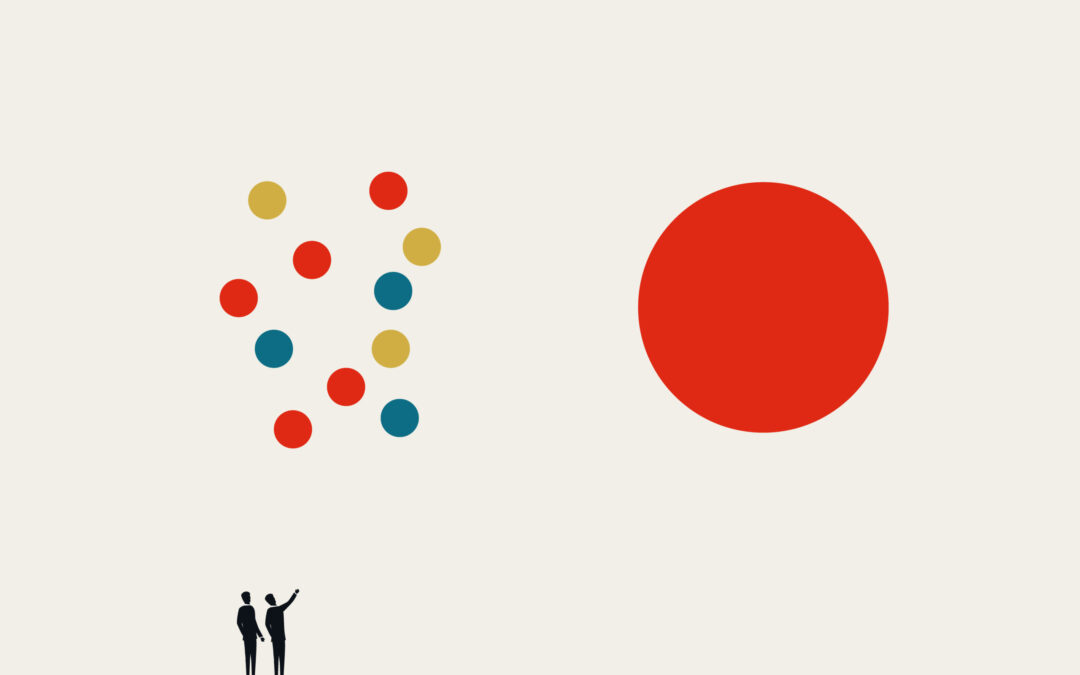

Surely, we may imagine, as we continue to add relevant, diagnostic information to our argument, we continue to strengthen our case. We may imagine this process behaving like rocks added to a bucket. Sure, the large rocks are heaviest, but the smaller rocks still add weight — and that weight can really add up.

The Averaging Effect Leads to the Dilution Effect

But as you may have guessed by now, that is not the way our brains process this kind of information. Curiously, rather than adding weight to our case, weaker arguments (despite being diagnostic) reduce the overall heft of our case in a phenomenon called the “averaging effect.” And when we’re mixing weaker arguments in with our strongest arguments, we can clearly see how the averaging effect leads to the dilution effect.

If you’re like me, you’re probably remembering countless meetings and presentations in which these two ideas were demonstrated to disastrous effect; and a few in which they were demonstrated to brilliant effect (whether intentionally or not). And you’re also probably beginning to imagine how the purposeful application of these ideas can transform the way we — and our organizations — communicate.

We are constantly trying to influence decisions — whether they’re the decisions of customers and consumers, the various large and small decisions made by and within organizations, or the constant internal decision-making we engage in as leaders. Let’s consider each of these, starting from the inside and working our way out.

How to Strengthen Our Position & Ability to Communicate

In our own minds, we are always seeking clarity — trying to reduce the fog around each decision as we steer our organizations. What would happen if we engaged in a mental exercise where we limited our arguments for and against a given course of action to just one each? What if we forced ourselves to consider only the single strongest arguments head-to-head before allowing any other arguments to filter in? Now that we’re aware of how our brains process information in this context, how can we prevent ourselves from being tricked by our own psychology? How can we experiment with information to parse out the effects of dilution and averaging in our own minds?

I believe the first step is to continually sharpen our ability to separate diagnostic and nondiagnostic information (the proverbial wheat and chaff), so we are less mentally susceptible to the dilution effect. Next, we should hone our ability to rank the relative strengths of various arguments, allowing ourselves to filter out weaker arguments and avoid the averaging effect. I suspect that approaching our internal decision making with these ideas in mind will only serve to clarify our outlook and, ultimately, strengthen our ability to communicate our position to others.

Imagine, also, how these ideas could impact organizational communication. What if everyone arrived to meetings prepared to collectively defend their decision-making process against the dilution and averaging effects? What if we all became experts at calling out the non-diagnostic information and removing it before diving into a course of action? What if teams engaged in the hard work of clarifying their strongest arguments before making presentations, allowing for a more streamlined decision process, rather than flooding the zone with data that may or may not be helpful? What would result from developing a culture that values a deep awareness of these effects and a commitment to filtering them out, both personally and collectively? Less group-think? More strategic clarity? Stronger buy-in? Greater autonomy?

Distill, then Distill Again

Ultimately, we must seek influence beyond the walls of our organizations, and by now we know that, as Niro Sivanathan points out in his presentation, when we want to influence, it’s quality over quantity. Far too often, despite offering great products and great services, and partly as a result of offering great products and great services, organizations choose to communicate everything that makes them great. Can you see where this is going?

Too often, we don’t go far enough in learning exactly what our customers need — what leads them to make one decision over another. Instead, we settle for one-size-fits-many communication, in which we combine our arguments, blast them all out together, and trust that the information most influential to each customer will reach them with its full force and clarity. And as we now know, this isn’t how it works. Instead, our customers — and let’s include here our partners and stakeholders — will experience, at best, an averaging effect; and at worst, a dilution effect, depending on how relevant all that “other” information is to their needs.

Across all of these levels of decision-making and communication, we need to seek the opposite of dilution. We need to insist on distillation. This doesn’t mean over-simplification; and it doesn’t mean putting all of our eggs in one basket. But it does mean becoming sharply aware of how our own minds process information that leads to decisions; and in turn, how our organizations process information that leads to decisions. And ultimately, it requires learning more about how our customers make decisions, so we can distill our argument to its most influential essence and leave average in the dust.

Richard Spoon

President, ArchPoint Consulting & Chairman of the Board, ArchPoint Group