Back when the modern technology game started, the vast majority of costs to companies went to hardware and communications, with software and people making up only a small portion of the total. These days, however, the majority of costs (80 percent according to Gartner) are in the people part of the technology equation—people who work to support, install, operate, integrate and decommission the technology needed for the company.

“The hard truth is that there is no one right technology solution for any company and saving money in hardware, software or communications, and the expense of labor such as support or integration costs, generally results in a lose-lose,” said Blair King, managing partner at ArchPoint Consulting.

While there is no silver bullet, there is a best practice for making technology decisions and integrating various software and hardware for a company’s needs.

And then there’s the wrong way:

In about 80 percent of organizations, the project manager makes the decisions about which software will work for his or her division or effort. Sounds reasonable, right? Wrong. The project manager understands the needs of a division and project. While that much is true, when a project manager makes a technology decision, it usually leads to disastrous results.

“The important part of IT decisions turns out not to be so much about how various software currently work and work together, as it is about figuring out the endgame,” said Kevin Quincey, partner at ArchPoint. “The important question to ask is, ‘where does the company need to be—and how to get there?’”

Having more discipline around IT will save the company a whole lot of money. In fact, there are four standardized levels of technological maturity for companies, and according to Microsoft’s and Gartner’s research, there’s a 7 percent difference in the return on assets when comparing all the companies surveyed who find themselves in the first level of technological maturity to the companies ranked in the third level.

“The crux of the matter in improving a company’s technological maturity rating is in getting the right decision makers involved—a company’s senior leadership. Generally, they’re the only ones who can see enough of the big picture to understand the potential gains and losses of the IT landscape,” said King.

Both King and Quincey have walked numerous CEOs and CIOs through the process.

“Once presented with the facts an IT assessment unveils, almost every CIO realizes his or her organization needs to significantly change the way the company approaches technological decisions,” Quincey said.

An IT assessment serves as a canary in the coal mine for both CEOs and CIOs as to the importance of taking a look at a company’s technological infrastructure. The struggle for many, of course, is the lack of access, whether real or perceived, in delving deep into the technology side of business. CEOs and CIOs who realize the difference an IT assessment can make in increasing value, improving process and integration are ahead of the game.

“For some companies, the integration of technology doesn’t involve a long or even short-term plan—it just happens,” King said. “If the company needs an email system, someone selects and buys an email system. If they need a billing system, someone else selects and buys a billing system. If they need a time management system, another someone selects and buys a time management system. Oftentimes, little thought is given to how each of these systems works together.”

However, after the software purchase takes place, people within the organization begin to realize, usually very quickly, that none of the systems were made to work together. Unfortunately, a lot of companies make this realization after they’ve made a large investment.

“Granted, some companies do a degree of research and still choose to piece mill their tech needs from various companies and software producers. This option isn’t cheap,” Quincey said. “However, other companies choose to make an even larger investment with a single company. A lot of businesses shy away from purchasing the various systems from one producer because the solutions initially look so expensive. Yes, they can buy the pieces separately for a lot less—but the money then comes in integrating the various systems.”

Making these decisions are tricky. Not because the division needs are misunderstood, but because there must be consideration into how the new software will actually work or how it integrate in to other parts of the company. The decision to purchase new software needs to come down to an IT person who works closely with the specific division of a company— and understands what that division’s needs most. The IT role is often a “systems integrator” or specialist in the architecture team and has spent his or her career in opening boxes and testing software.

Most companies have to make software decisions about 100 times a year—on top of the existing web of programs and software solutions. The issue is not simply a matter of how and what software comes into an organization. It’s also an assessment of the current situation.

So, where does a company begin? The first step is assessing your company’s current landscape. Believe it or not, a complete technology assessment is less complicated than you might expect. Using a 75- to 80-question survey, composed of mostly yes or no questions, trained experts can determine where a company falls on the five core capabilities on an industry standard technology maturity model.

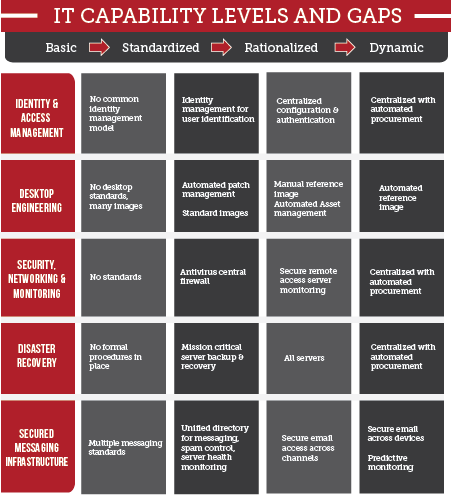

The five core IT capabilities are:

- Desktop management

- Identity and access management

- Security networking and monitoring

- Disaster recovery

- Secured messaging infrastructure

The four IT maturity levels are:

- Basic—This level is complete chaos in technology decisions. The company has no desktop standards and allows people to make decisions on a local or regional level regarding software. No security standards or formal procedures for disaster recovery are in place.

- Standardized—This level is characterized by tight control. The company allows little to no room for anything to happen for special circumstances or to satisfy local/regional needs.

- Rationalized—Allows global flexibility and secure remote access server monitoring. All servers have disaster recovery capabilities. Secure email access across channels.

- Dynamic—Values both local and global flexibility by efforts to organize the critical decisions locally with centralized automated procurement. Values local flexibility and some will value global capabilities.

Combining the five capability areas with the four maturity levels produces this chart:

“Few customers make it to level 4,” Quincey said.

In fact, Microsoft ranks only about 2 percent of their customers at level 4—a fleeting glory because technology changes so fast that those who make it to level 4 don’t stay there for long, according to King.

The infrastructure optimization model offers a way to break down a company’s technology situation into four levels—immature, medium, mature and advanced. Once a company participates in a complete IT assessment, CIOs realize the need to move the company up two maturity levels in various capabilities.

“While it’s not impossible to move quickly or less expensively, the key point is that the assessment model provides a company a clear overview that helps reorder how to tackle the major renovations,” said Quincey.

The end of the IT assessment story is the most important part. Without a global view of what difference an IT assessment and plan can make, a CEO may not even care about assessment not because he or she doesn’t care but because other more pressing issues occupy their time and energy.

Assessing your capability

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how well does IT support your business portfolio?

- On the IT Capabilities and Gaps, gauge your organization’s maturity level.

- What gaps do you close?